The honest ramblings of a student of architecture

Oh, are you finishing 12th standard? What’s next?” “I’m going to architecture school, Aunty.” “So you’ll be doing my new cow shed, then?” “Of course I will, Aunty!” This is me at the beginning of my architectural journey when I’m not sure what this profession entails. There are five years to be spent in the architecture college, so I figure that somewhere along the way, the answer would come to me..

Phase 1: I’m going to design houses.

Since the eighth standard, I’ve had a growing fascination for architecture. I’ve spent my summers making cardboard models of my dream home, creating nooks to read my books, having a giant tree in my bedroom, and even planting an aquarium in between all this. There is a rush of excitement now that I am in my 12th standard. My decision to be an architect is readily approved as my mathematics scores are ‘too good to waste on the Fine Arts’. Hence, my love for drawing + my good scores = architecture; added up well.

Phase 2: Unsure, but I love this!

I’ve enrolled myself in an architecture college and realise that designing a cow shed is actually a respectfully serious and complex task at hand! Off late, I am developing more skills. I am sketching, cutting, sticking, tearing, carving, printing and doing a whole lot of other things I never thought I would do in an architecture college. The subjects range from structures to sociology, from printmaking to construction. There are times when

we even follow cows around

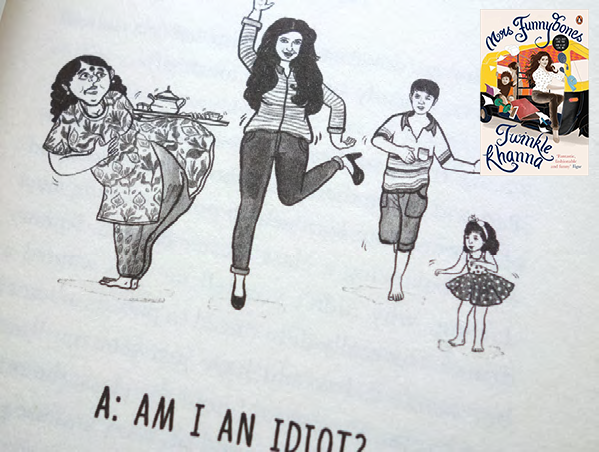

Phase 3: No, I’m not an Engineer!

I have to explain how I am learning to design ‘buildings’, as my mundane explanation seems to dilute the richness of this profession. Nobody is amused by my tale of following the cows. Sometimes I just nod in defeat every time I am introduced as an engineer. I need some help; hence, I resort to the internet. “An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings”. NO, NO, NO! That’s not right! (For future reference, stay clear of Wikipedia definitions if you don’t want to be torn apart by your architect friends). Defeated, I go back to my chants of “I’m learning how to design ‘buildings”.

Phase 4: I’m a master of space

I pore over texts glimpsing into the history of the profession and its vague beginnings, where the carpenter was sometimes the architect while at other times there was no real difference between an architect, an artist, and a sculptor. Over time, I begin to feel the power that rests in an architect’s hands. He is the master of space, a creator of dwellings connecting them to the sky and the earth aesthetically, and weaving together an experience.

Unfortunately, my newfound understanding amuses only myself. If a doctor told you how he is ‘the healer of not only the physical body but also the mental soul aided by his knowledge’, you would roll your eyes and respond with, “I have a health problem and you fix it”. The search for a definition is my search for understanding, and there is no need to force that upon anybody else.

Flash forward to the present, where I’m explaining to a curious group how I design ‘buildings’, and they congratulate me on my first project. This is easier, but through the nods and smiles, I decide that I wouldn’t mention that I am indeed designing that cow shed.

Words and Illustration by Leeza John